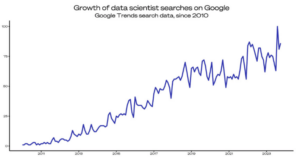

Data and its impact on our daily lives increases exponentially every year — from how we consume news and information, to the way we engage with each other via social media, to how we transact for goods and services online. From sensor readings, machine learning, and the prevalence of AI-powered natural language processing and image generation, the daily volume and variety of data being created and parsed is extraordinary. This upsurge has led to a global recognition of the value of data science skills across all industries.

A recent report by ExcelinEd and the Burning Glass Institute underscores the increasing demand for data science skills in the U.S. job market. According to the report, nearly one in four job postings in 2023 required at least one data science skill, with some states seeing even higher percentages.

Across industries and countries, organizations are realizing the potential of data-driven insights to drive innovation, improve efficiency, and gain a competitive edge. “Historically, employers seeking workers with data science skills were largely operating in a small collection of industries and sectors mostly focused on science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). Over the past decade, however, that has changed. Today, to varying degrees, data science touches every American industry. Between a quarter and a third of job postings seek workers with different data science skills – sectors far outside the scope of tech.” (Data Science is For Everyone, Burning Glass Institute, February, 2024)

The global demand for data science skills is reflected in the growing number of job openings for data scientists and related roles. According to a report by the World Economic Forum, data and AI-related jobs are among the fastest-growing occupations, with an expected 11.5 million new jobs being created by 2026. This growth is driven not only by the increasing volume and complexity of data but also by the recognition that data science skills are essential for driving innovation and staying competitive in the digital age. From healthcare and finance to manufacturing and retail, the ability to collect, analyze, and interpret data is becoming a critical skill for success in the modern economy.

The demand for data scientists is particularly acute in industries undergoing rapid digital transformation. For example, in the healthcare sector, data science is used to develop personalized treatment plans, predict disease outbreaks, and improve patient outcomes. In the financial industry, data scientists are leveraging machine learning algorithms to detect fraud, assess credit risk, and optimize investment strategies. Even industries once considered far removed from data science, such as agriculture, are using it to optimize crop yields, reduce waste, and improve supply chain efficiency. In construction, data scientists leverage sensors and machine learning to monitor safety conditions, predict maintenance needs, and improve project management.

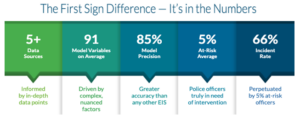

Specific to data science applications within law enforcement, Benchmark Analytics has been at the forefront — with first-of-its-kind technology that has transformed how agencies manage their personnel and mitigate risk exposure. First Sign® — our data-driven, research-based early intervention system (EIS)—is designed to help agencies use the power of data to identify officers who may be at risk of engaging in misconduct or experiencing mental health issues. By analyzing a wide range of data points, including use-of-force incidents, citizen complaints, and performance evaluations, First Sign can alert supervisors to potential problems early on, allowing for proactive intervention and support.

The benefits of data science in law enforcement extend beyond operational efficiency and risk reduction. By embracing data-driven approaches, agencies can also enhance transparency and accountability, building trust with the communities they serve.

However, integrating data science into law enforcement personnel management requires guardrails for implementational success. Ensuring the privacy and security of sensitive data is of the utmost importance, requiring robust data governance policies and secure infrastructure. Additionally, thorough system training ensures that supervisors have the necessary data literacy skills to effectively leverage these tools and interpret the insights they provide.

As the demand for data science skills continues to grow worldwide, law enforcement agencies that embrace data-driven approaches are better positioned to meet the challenges of the 21st century. When agencies partner with Benchmark, they unlock the full potential of their data to create an accountability and officer support system that boosts morale and increases retention . . . reduces internal agency resource needs . . . and ultimately improves community relations.

The future of law enforcement is data-driven. At Benchmark, we’re committed to helping agencies leverage data science for elevating their overall agency performance. Contact us today to learn more about how our team of data scientists and data-centric solutions is helping agencies make more well-informed decisions about how they manage, support, and elevate their workforce.

Law enforcement personnel have a unique position in our society. They are responsible for the safety and security of all those who reside in, work in, and visit their jurisdictions. As such, they have great responsibility to carry out their duties and exercise their authority within the bounds of established policies and procedures, which are an essential component of any law enforcement agency. Policies address pertinent matters, such as what entails acceptable behavior by employees. Procedures within a policy define a sequence of steps to be followed in a consistent manner — for example, the actions that need to be taken for an out-of-policy event.

Law enforcement personnel have a unique position in our society. They are responsible for the safety and security of all those who reside in, work in, and visit their jurisdictions. As such, they have great responsibility to carry out their duties and exercise their authority within the bounds of established policies and procedures, which are an essential component of any law enforcement agency. Policies address pertinent matters, such as what entails acceptable behavior by employees. Procedures within a policy define a sequence of steps to be followed in a consistent manner — for example, the actions that need to be taken for an out-of-policy event.

Safety. Specifically, the gathered team was seeking to assess the current state of data collection, use, and transparency practices in law enforcement agencies across the country.

Safety. Specifically, the gathered team was seeking to assess the current state of data collection, use, and transparency practices in law enforcement agencies across the country. The success of a consent decree, in large part, hinges on how policy changes are implemented, documented, and reported. While they have little input on the consent decree terms, chiefs and departmental leaders are in the driver’s seat when it comes to fulfilling the terms of the decree and those of the monitor.

The success of a consent decree, in large part, hinges on how policy changes are implemented, documented, and reported. While they have little input on the consent decree terms, chiefs and departmental leaders are in the driver’s seat when it comes to fulfilling the terms of the decree and those of the monitor. Without intentional and research-based data collection and analysis practices, policing leaders are effectively flying blind when shaping policies and allocating resources within their agencies. Just as troubling, they may miss out on substantial cost-savings that often come with an investment in their data science capabilities. This article looks at the basics of data science in law enforcement and its potential to guide meaningful and positive changes in law enforcement.

Without intentional and research-based data collection and analysis practices, policing leaders are effectively flying blind when shaping policies and allocating resources within their agencies. Just as troubling, they may miss out on substantial cost-savings that often come with an investment in their data science capabilities. This article looks at the basics of data science in law enforcement and its potential to guide meaningful and positive changes in law enforcement.